“We Make Something Everyday”

“I didn’t think it would come here,” Raelynn Cachini said, at her home on the Zuni Pueblo reservation near Gallup, NM. “But it did. And we were ready.”

“It” was Covid. By early April 2020 the first Covid cases were confirmed in the Zuni, with the concern that it could lead to the eventual extinction of the tribe if no safety measures were followed. The Zuni reservation houses 7,590 tribal members. In a small, close-knit community like this, just one death sends shockwaves, let alone more.

“A few months ago there were five or six deaths per week,” said Raelynn. “We were on weekend and night curfew. So many people were bored! But I was so busy making masks.”

Raelynn started sewing at age 12 and began making tribal regalia a few years ago when her now seven year old son began learning traditional Zuni dances at Head Start. He needed the custom colorful outfits that characterize most tribal “fancy dress” dance regalia, which are sewn individually for the wearer and reflect their familial and community ties.

Raelynn’s aunt taught her the basics of regalia sewing, including how to make a dress pattern and cut down an adult shirt pattern to a child size. She learned how to make her own binding (bias tape) and was pulled deeper into Zuni traditional dress, which is a living symbol of the intricate matrilineal clan system and significant transition points for a tribal member.

When a Zuni child is born, their lineage starts in the mother’s clan and is welcomed into the father’s clan. The aunts (“aunties”) from the father’s side become the child’s godparents, welcoming them into the new life with a traditional outfit made either by themselves or commissioned from another tribal maker. If the child is initiated, there are dancing and religious ceremonies with more outfits made especially for the event. There are outfits for social dances, seasonal ceremonies, and individual spiritual quests. When a Zuni dies, another personal, final outfit is sewn, once again influenced by the aunties who have been the support system for the person’s entire life. They make the final decision on what the outfit should depict for a safe passage. From a maker standpoint, this stressed Raelynn the most.

“There were so many people dying, and I was worried more would go. I only had so much fabric and that was meant for regalia. I needed to save it in case I had to make passage outfits. The men need a white shirt and pants, the women need a dress, but there are more layers to go on top of that. I didn’t want to use up all my fabric for masks if I needed to make outfits for those who had passed on,” she said, as tears quietly appeared. “It was hard to know what to do.”

Help came first from the group Sewing For Navajo Nation, which donated 1000 mask sewing kits made from pre-cut fabric and elastic ear loops. Raelynn and the Zuni sewing community got busy. More fabric and elastic donations rolled in. The regalia makers, already hyped by a friendly internal competition streak over who could make the best traditional dress, turned that energy towards masks.

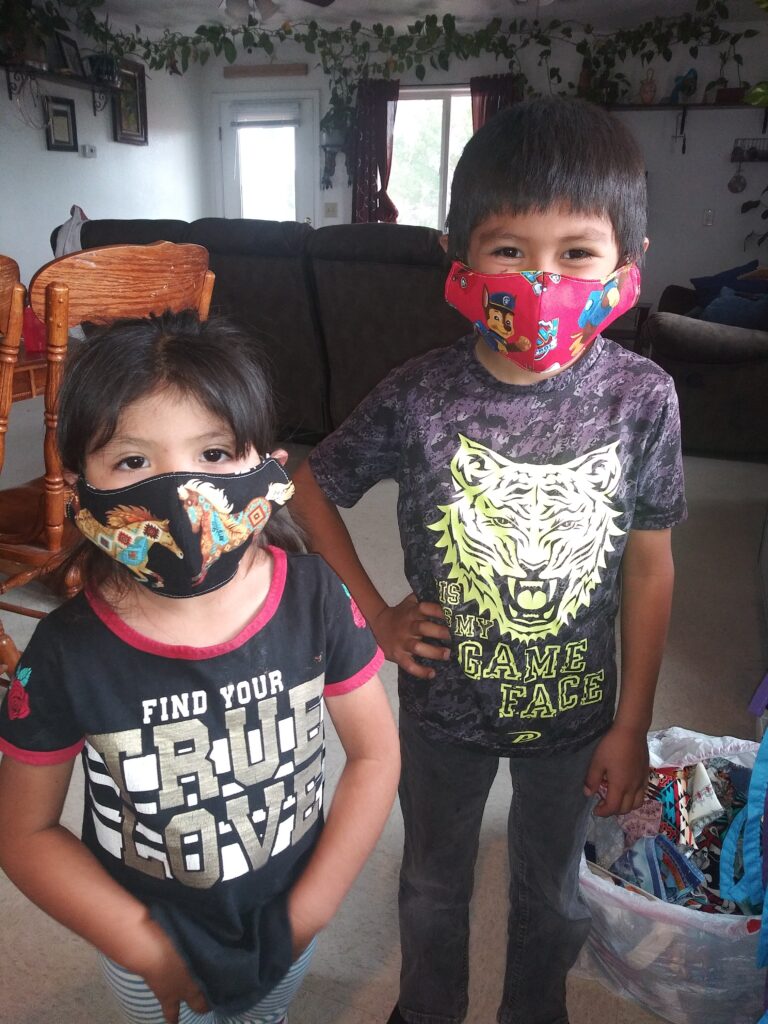

“We competed to see who could make the most masks in the least time, as well as match a mask to an outfit. They became a fashion statement.”

Some masks were sold, others donated. The Zuni senior center was overjoyed to receive 500 donated masks. Protecting the elders was a top priority, as they are often the gatekeepers to the traditional Zuni language. Due to social distancing efforts, simply going to the grocery store was a challenge if a tribal member didn’t have a mask.

“I heard about people being turned away at the store because they didn’t have a mask,” Raelynn said. “I couldn’t bear to think of someone going hungry because they didn’t have one, so I kept sewing.”

Covid brought an additional blow to Zuni traditions. Due to social distancing and hospital safety precautions, the traditional funerals and burials were severely curtailed because tribal members were unable to be with their loved ones when they passed or even see them for the last time. Communal events such as burials, seasonal ceremonies, or even group sewing events were not allowed in efforts to control the disease spread. For a culture that draws its life-blood from togetherness, this was one of the most heart-rending aspects of Covid.

By July, the Zuni sewing community had persevered to single-handedly mask the entire population, with citizens receiving multiple masks to last them throughout the weeks. Their regalia sewing expertise, especially in how to make handmade binding and pleated dress sleeves, helped them churn out a rapid production line. Compared to traditional garments, which can have intricate decorations, masks were a bit simpler.

“I think we made over 13,000 masks,” she said. “And it worked. Between the masks and the curfews, the cases slowed down in July and we had only 2 new cases in September.”

A silver lining appeared through the dark Covid cloud. Zuni who had been previously uninterested in sewing traditional garb suddenly clamored for instruction during quarantine. This was challenging, Raelynn said, because so many techniques were hard to teach over the phone or Zoom but had to be done in person, the type of gathering that Covid prohibited. Still, the mask making effort inspired new makers. Extra sewing machines were shared among the community and Raelynn is busy constructing the foundation for a life-long dream.

“I want to have a workshop with enough room for sewing classes, a place where people can see the fabric and different patterns, be inspired to make something of their own. All of us, the regalia makers, we make something every day. We want to teach everyone else what we know.” Covid has shown the Zuni how fragile their traditions can be and there is a burgeoning groundswell to preserve what could have been lost so easily.

That Elastic Connection

The mask making kits from Sewing For Navajo Nation (which by July 1st had donated over 107,000 hand-sewn masks to tribal areas) received donated elastic from an unlikely source. Back in the early decades of spring 2020, any mask making supplies such as white thread, elastic, bias tape and even fabric were in short supply. One day Sue Wilson, a fabric artist in the metro Atlanta area, got a call from her friend Rosemarie Szostak, PhD- who said she had all the elastic anyone could ever need.

“She asked me how much I wanted and I just went silent on the phone,” Sue said. “I said, 50? Yards? Because that was an enormous amount we couldn’t get in stores. And she said that was a tiny scrap compared to what she actually had.”

As luck would have it, three years ago an underwear manufacturer near Rosemarie closed their factory, moving production to India. This left massive trailer loads of high-grade, lingerie quality elastic- “soft as silk”- on the potential way to the landfill. Rosemarie couldn’t bear to see that happen and rescued it all, along with boxes of white thread, and cozily stored everything away in a barn on her property until Covid hit. Sue immediately began donating elastic to mask-making groups and tracking production on a spreadsheet. To date, over 133,000 masks have been made from the Rosemarie elastic. Sewing For Navajo Nation individually received enough to make 9,000 masks, which eventually trickled down to kits sent to the Zuni reservation.

In addition to being a pandemic elastic supplier, Sue Wilson turned her pre-pandemic fabric skills to masks- just like another production sewist, Cathie Foard from Garland, TX. Both women are chapter participants in Days for Girls, a non-profit that supplies hand-sewn fabric menstrual pads (distributed via kits) to women all over the world. Sue and Cathie are experienced pad makers and switched to masks as their local medical communities were in crisis during March.

“I’ve personally made over 2200 masks since March, many of them for Methodist Regional Hospital,” says Cathie, a retired special education elementary teacher. “And I’m working on completing a 3,000 mask order for the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate. I look forward to sewing the masks as it gives me a chance to play with my pretty fabric. I enjoy making every single mask, especially the child-sized ones. Their needs are very close to my heart.”

As a formal national fundraising manager, Sue Wilson has ended up with a finger in every mask making pie. Part of fifteen Facebook mask groups- “and I’ve never seen a political post on any one of them”- she has been working almost non-stop since March. Personally sewing for her local community (which produced about 11,000 masks by the end of May) she helped a sister county with their 45,000 mask production.

“There was a frenzy in March,” both Sue and Cathie said. “It was unlike anything we had ever seen in our lifetime. A spirit arose, a camaraderie that brought us all together for a common good.”

By mid summer the frenzy slowed down slightly and the women turned back to more menstrual pad (and mask) crafting for Days for Girls, shortly before the Beirut blast on August 4th. Over 12,000 menstrual hygiene kits and masks were sent to Lebanon, which suffered a severe shortage of soap, shampoo, toiletries, and feminine hygiene products due to the destruction of the port.

Now that national mask making efforts have slowed, groups are directing their talents to new challenges. Sue and Cathie have turned their efforts to organizing child-sized mask production for Oklahoma tribes, which need 13,000 masks.

“I put out the call and in a few hours I had 70 people sign up,” Sue recounted. “Groups that have stopped local production are donating fabric. We will need SO MUCH fabric for this order! I think a few see this as their second chance to be involved. They weren’t able to help when Covid first hit, now they want to join with this second wave. It keeps me up at night, sometimes, thinking about protecting the children.”

To help make masks for indigenous people, please join Sewing for Native Peoples, which is currently working on a 13,000 child mask order for Oklahoma tribes. If you have mask-making fabric to donate, especially pre-cut masks, or any other sewing supplies, they would be gratefully accepted.

To coordinate donations of warm blankets, coats, and firewood to Zuni elders, please email togetheronturtleisland@gmail.com

A great article. I consider all 4 of you, Rae, Catherine, Sue and Victoria as modern day heroes. I guess we will never know how many lives have been saved, but I honor you 4 for all you have given.

This is a inspirational COVID story. Still sad about the death COVID caused to the people in this area but also very powerful in the way they came together and even got back to traditional roots.

From a dear friend of Sue Morse Wilson:

Sue, whoever wrote this piece did a BRILLIANT job of telling this unique and very important story!

Tears welled up in my eyes as I read the article.

I am humbled by the work you and Cathy have done…because there was a need and it was “the right thing to do” .

The Universe came together for this extraordinary effort to aid the most disenfranchised segment of the American population!

The article is so well written because of its tempo. It kept building on the facts and kept the reader interested to know more! By the end, the reader wanted to know “how” they could become involved or how to contribute via

$$$!

So uplifting!!!