OSMS has studied how maker communities of different countries individually responded to the crisis. We explored how they solved problems specific to their geography, society and other factors. We provide the resulting insights in the form of individual national case studies for free, vetted for accuracy by the respective national maker communities. These case studies serve as a blueprint for maker groups in countries that want to establish or improve nation-scale coordination.

1. History

Image: OSMS

India has a population of 1.353 billion people.

Before COVID, many makerspaces existed around India but they were rather small and activity was limited. Lab operators had challenges operating the labs independently because of financial sustainability concerns, so most labs were parts of a university. Some micro-labs were even run out of private homes.

Since 2013, Maker’s Asylum in Mumbai was a rapidly growing, openly accessible makerspace, founded by Vaibhav Chhabra. He had lots of international friends that inspired him to start the lab; one of them being Gui Cavalcanti who had shown him a sustainable model with Artisan’s Asylum in the United States.

Image: Maker’s Asylum

There are only 4-5 “proper” makerspaces in India, but there was collaboration with university labs beforehand. Personal relationships between founders of said university labs and makerspaces existed, as did some WhatsApp groups, but no concrete inter-organizational partnerships had been built. There was simply never demand for a India-wide collective or coalition. The only larger-scale conversations had centered around collaborative attempts to start a Maker Faire or Makerfest in India.

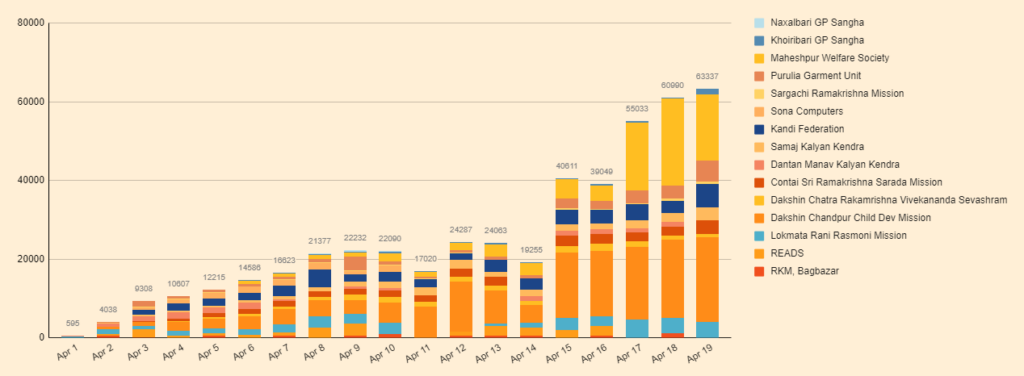

When COVID broke out, some makers began looking for ways to help. The earliest efforts were mask sewing related, with one of the largest maker-led initiatives being started by Soham Sarkar and sponsored by the local government of West Bengal. This initiative was run together with the Department of Self Help Group & Self Employment, and featured around 20 self-help groups around Kolkata as well as unemployed youth recruited by government officials; collectively, they produced 477,316 cloth masks from April 1-April 19; that is 26,517 masks made per day. The initiative stopped after less than 3 weeks because the local government could no longer sustain funding it, but its production scale – nearly half a million pieces of PPE made in distributed manufacturing among private individuals in 18 days – can partially be attributed to the fact that individuals were earning income in exchange for the mask-making.

The earliest face shield prototypes were built around March 23. Vaibhav joined OSMS at around that time – due to his existing friendships with the international maker community – and then figured out how to go about taking the international lessons to India, and turn Maker’s Asylum into a PPE factory.

Doctors in Bangalore requested PPE prototypes from Maker’s Asylum in Mumbai, but once the builds were complete, it took 3 days instead of a few hours for the shipment to arrive at their destination. It became clear very quickly that the distribution and shipping systems of India had been severely interrupted, and localized production became the modus operandi.

Image: M19 Collective

The next hurdle was that international makers had zeroed in on distributed 3D printing as the primary mode of rapid response production for face shields, but in India there were only 1-2 3D printers per lab usually. 3D printers are exclusively manufactured abroad, and importing is expensive – so this wasn’t going to work as a large-scale solution for India’s maker community.

The Asylum team realized quickly that there was a better route to go: there are hundreds of laser cutting shops in India, and the machines are built domestically – so they repurposed designs, and rebuilt them for laser cut face shield frames. They went through 21 design iterations of the face shields to come up with a design that could use locally available, inexpensive materials and technology to help scale the production as volumes required in India were pretty large.

Once these early technical challenges were solved, Richa Shrivastava Chhabra, managing partner at Maker’s Asylum and former local government organizer, pointed out the need for visibility and dedicated herself practically full-time to outreach and marketing. She started a campaign of social media work and sharing designs with other labs. This further turned into creating videos to show the Face Shield assembly line at Maker’s Asylum and let other labs around India copy their work. Richa reached out to labs one by one, encouraging them to join efforts and work together.

The team grew quickly, and many decided to pack up their bags and literally started living in the Asylum. Volunteers came in and started living with them, like a Goldman Sachs Analyst, a Neuropsychologist, an orthopedic surgeon etc.

Volunteers came from surrounding regions to join them; the team had to actually buy a physical map since volunteers came from distant villages that nobody on the team could locate. Children started posting videos of themselves making face shields at home, and in turn pulled other kids into the effort, as did a doctor in a distant city who then recruited his medical students to build together with him. A filmmaker in Guwahati started making these in his house with a few volunteers there. Most of these relationships were made from scratch for the crisis, and people started reaching out more and more.

The team at Maker’s Asylum often worked until 2-3am and woke again at 6am, with a production line that ran like clockwork. Inside of the Asylum, 15-20 tables were occupied with people working non-stop.

Image: Maker’s Asylum

This increasing momentum and motivating environment, as well as the offers from other makerspaces and labs to join forces, led to the M19 Collective which organized around the Maker’s Asylum. Richa’s team performed enormous amounts of manual outreach and training work to get different groups on-boarded on the production process and then replicate the model in distant parts of India. 42 partners got involved in the collective; about 10 of them were university labs.

The national lockdown in India was quite severe, which made it very challenging to transport shields from one region to another. Cities issued PPE demand letters which gave the M19 collective special access to shipping across regional borders.

Another method to speed up delivery was that ambulances would be sent by hospitals, and police cars sent by local government; they’d wait in a line outside the Maker’s Asylum doors to pick up and directly PPE as it ran off the production line. The coverage of the M19 Collective was across India, at least 1 lab per state, and a total of 42 cities and villages participating. A concentration was mostly around the area where they lived. Social media following was a huge part of this to amplifying the collective, and a network effect of people that they either knew, or others that found out about them.

India had another barrier – language, with hundreds of dialects being spoken across the subcontinent. However, most tech-savvy people in India speak English. The emerging WhatsApp group that was used to connect the M19 leadership was in English, the M19 update videos were recorded and published in multiple languages.

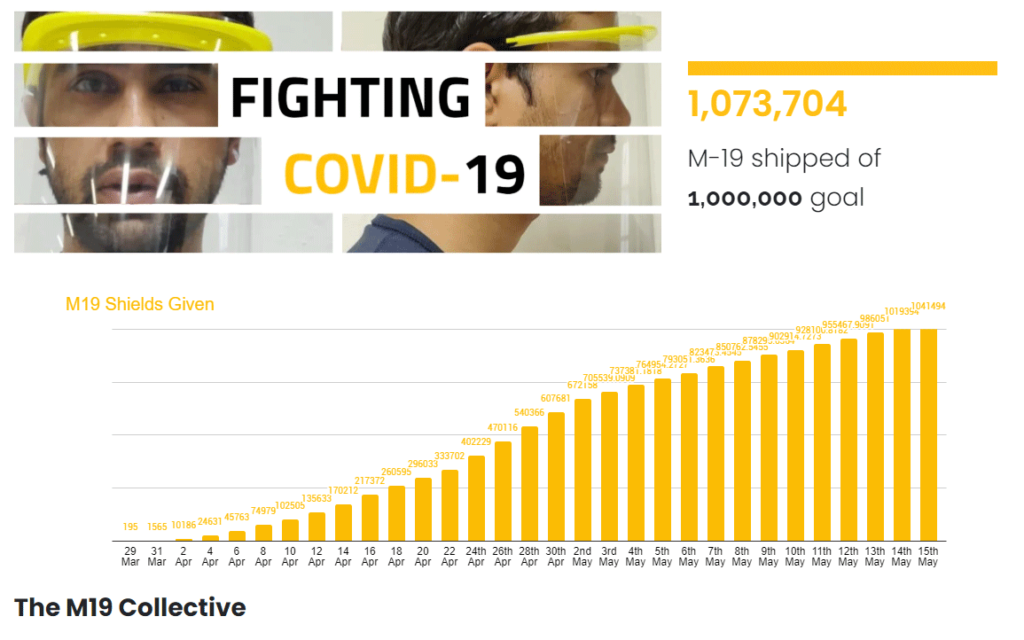

The M19 collective produced over a million face shields in its operation, and its hubs were located across the entire country. They went as far as sending donations to Kenya, the UK and Mississippi. However, in late June 2020, Mumbai’s COVID cases increased dramatically and the team decided that the only safe way forward was to shut down the physical space of the Asylum. It was too risky to meet at this point, since the entire model was based on a dormitory-style manufacturing line.

Image: Maker’s Asylum

The team is now transitioning to an online operation with online classes; they are anticipating a 6 month hiatus at least. The M19 Collective consisted of lots of different kinds of people, but many of them had to go back to work with the ending of the lockdown.

Manufacturing industries have successfully taken over PPE production in India (and the M19 collective was a successful stopgap as planned), so now the Asylum members are working on PAPR designs (the M19 MAPR project) since they are important in medical facilities yet extremely expensive to purchase in India. A single PAPR unit usually costs $2,500. Since importing is extremely expensive, the solution was once again to locally build them in India.

Bunny PAPR sent 20 copies to India so the Asylum team can improve their design going forward.

2. Management /Reporting Structure

All members of the M19 collective reported directly to the Maker’s Asylum which became the organizational focal point, while physical production happened in a decentralized way. Local connections helped at the get-go to form relationships; Richa and the outreach team helped each group first understand how to run things, and once they were on-boarded and successfully understood how the group worked, leaders were added to the private WhatsApp group.

WhatsApp is the preferred method of communication in India, and was also the primary communication tool among M19 Collective member leaders, and a shared Google Sheet was used to track production. YouTube, Facebook and Instagram were used to distribute marketing videos and do general outreach.

At the height of operation, the Asylum alone received 100-200 calls per day from labs and hospitals, so the full-time dedication to communications was what made an effort of this scale possible.

While approx. 100 leadership staff were on one giant WhatsApp group to coordinate M19, each lab managed their own volunteer group internally. Many groups needed organizing and coordinating help/hand-holding to get demand information and learn how to work with donors.

3. Data Management

The collective managed a shared Google Sheet to feed data onto their data visualization statistics on the website; it primarily tracked Face Shield production, totaling more than 1 million shields.

Image: Maker’s Asylum

There were further initiatives in India – for example, 477,000 Face Masks were built by a group run by Soham Sarkar. Data was collected into an Excel spreadsheet on a daily basis, broken down by regional affiliates. Despite only lasting 18 days, the initiative ramped up very quickly to an industrial scale.

Image: OSMS

4. Politics & Enablers

Many local government, law enforcement, medical personnel and private companies supported the efforts in their local region. In West Bengal, the Department of Self Help Group & Self Employment financed and supported the production of 477,316 cloth masks.

The M19 Collective figured out how to win bids with the Indian government’s public tender process, so they could respond to official requests for equipment, and receive funding for production. The collective, once the core group in Mumbai had mastered the tender process, trained other hubs around India to respond to the public tenders in their regions. The Collective features the following institutional users and supporters on its website:

Image: M19 Collective

5. Funding

Image: Maker’s Asylum

Soham Sarkar’s initiative with the West Bengali government received funding from the government, which not only covered materials but also labor. While the initiative was short-lived due to funding running out after 18 days, the speed of production (half a million masks in less than 3 weeks) can be attributed to the payment of individuals through the funds set aside by the local government.

The M19 Collective started a fundraiser online, figured out a price per shield to both finance materials as well as reach financial sustainability for the space. The price was 55 rupees, about $0.75 cents per shield. They were very careful about pricing to make sure it stays affordable. Some people were buying shields privately if they could afford it, and others received the shields as donations.

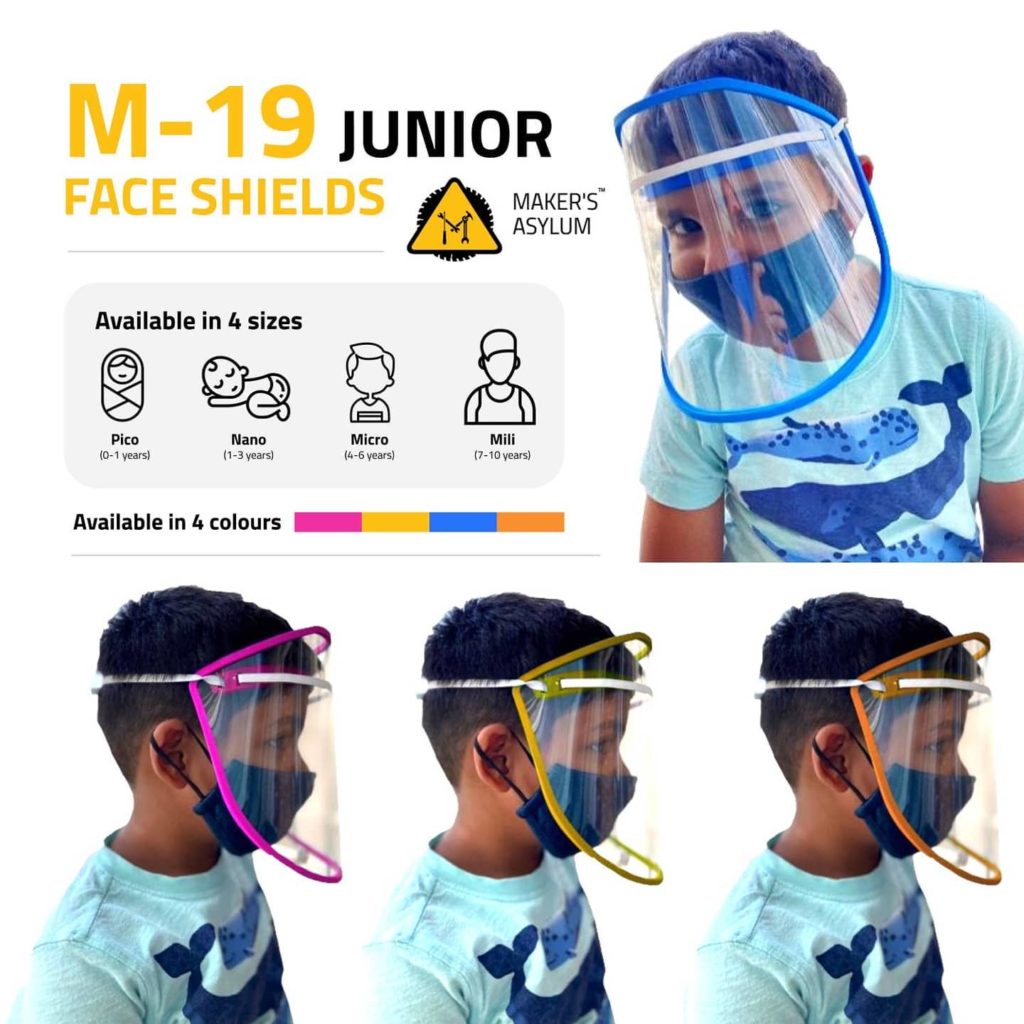

Maker’s Asylum found ways to financially sustain its operations. Once the lockdown in India was over, demand among common citizens needing face shields surfaced. So Maker’s Asylum opened an online retail store where they offer a variety of products apart from their initial #M19Shields, such as Junior Face Shields for infants and children, the active respirator M19 MAPR, educational kits for their online programs and more. They are now in the process of moving their physical space from Mumbai to Goa to reduce costs and keep innovating in the space of design, hardware and sustainability.

Image: M19 Collective

Links / Press

Read Further Case Studies

Brazil

Despite enormous infrastructure challenges, Brazilian makers have stood up a decentralized national response resulting in 1 Million + pieces of PPE made across hundreds of maker groups, with a growing nation-wide coalition.