OSMS has studied how maker communities of different countries individually responded to the crisis. We explored how they solved problems specific to their geography, society and other factors. We provide the resulting insights in the form of individual national case studies for free, vetted for accuracy by the respective national maker communities. These case studies serve as a blueprint for maker groups in countries that want to establish or improve nation-scale coordination.

History

Image: OSMS

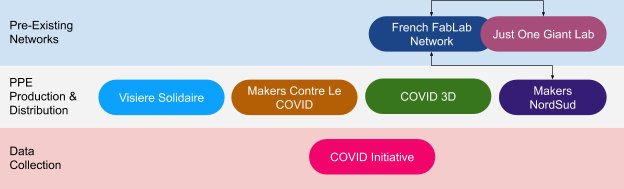

France has a population of 67 million people. Multiple maker organizations acting nationwide are collaborating on the national response of makerspaces against COVID-19. There are different types of organizations doing this national coordination work; makerspaces, research and development organizations, and communication-focused initiatives that all work together hand in hand. They all have loose ties to each other and have occasional video conferences to share ideas and work to optimize output and distribution.

In France alone, there were 238 FabLabs in the French Network at the point of outbreak, so there was a well-connected network, and many leaders used Facebook to communicate with each other. There was also an existing Maker Faire network. There were a number of mailing lists that had been established, but there was no map or proper data collection about how many people owned 3D printers. There was never quite a motivation to organize across sectors, so Makers and the interconnected FabLabs existed somewhat independently.

Ahead of most maker action, sewists started working nearly immediately after the outbreak. One doctor in France published a PDF for a mask through a radio channel which put it online. It spread like wildfire among the sewing communities. This trickled all the way to the French national norms agency, and they published a guidance that “if you sew a mask, sew this one”.

This nearly created a communication channel between open source medical supply organizers and the French government – but the government dropped the ball on the groups beyond that initial mask making PDF guidance. In the week between March 18-March 31, a number of initiatives popped up nearly simultaneously. Two main streams of Maker COVID responses established themselves – the Grassroots type, and the Preexistence type.

- The initial driver of most large French organizations was through existing social media followings and turned into organized grassroots movements:

- Groups like Visere Solidaire and Makers Contre le Covid were the first two large organizations that were able to first establish a nationwide following. They were formed through smaller forums that grew into national organizations that helped connect makerspaces with health care providers. They first utilized a Facebook Group and then formed their own websites. The grassroots group category still has a quite decentralized organizing style today.

- Monsieur Bidouille who was in the maker community utilized his large twitter following of other makers to create a forum called Entraide Maker to begin discussing ideas of how the maker community could help in the pandemic.This was a base blueprint for larger organizations that were started in its wake.

- Axelle of the popular Heliox channel on Youtube then followed up with creating guides and spreading them on how to create masks and face shields; this eventually led to the Covid3D project.

- The first big networks that organized already existed pre-COVID.

- Organizations like the French Fablab network already had a pre-established network of makers who had the capability of almost immediately distributing PPE blueprints and began to facilitate the creation of PPE by members of their networks.

- JOGL (Just One Giant Lab), a forum that facilitates the communication between professionals, students, and activists to come together on projects, created the Open COVID 19 Initiative which was an open source forum that allowed contributors to share and discuss blueprints for creating new PPE (personal protective equipment) like masks and visors. They had a pre-existing network and therefore was able to more easily set up their COVID initiative and quickly R&D new solutions. These think-tank companies were able to communicate with makerspaces to connect them with bio-labs, who in turn offered their facilities to help test various plans and organizations.

- MakersNordSud utilized the existing FabLab networks of 6 member organizations including 8 West African countries’ FabLabs in order to facilitate an equipment and skills transfer from France to Africa in order to build PPE there.

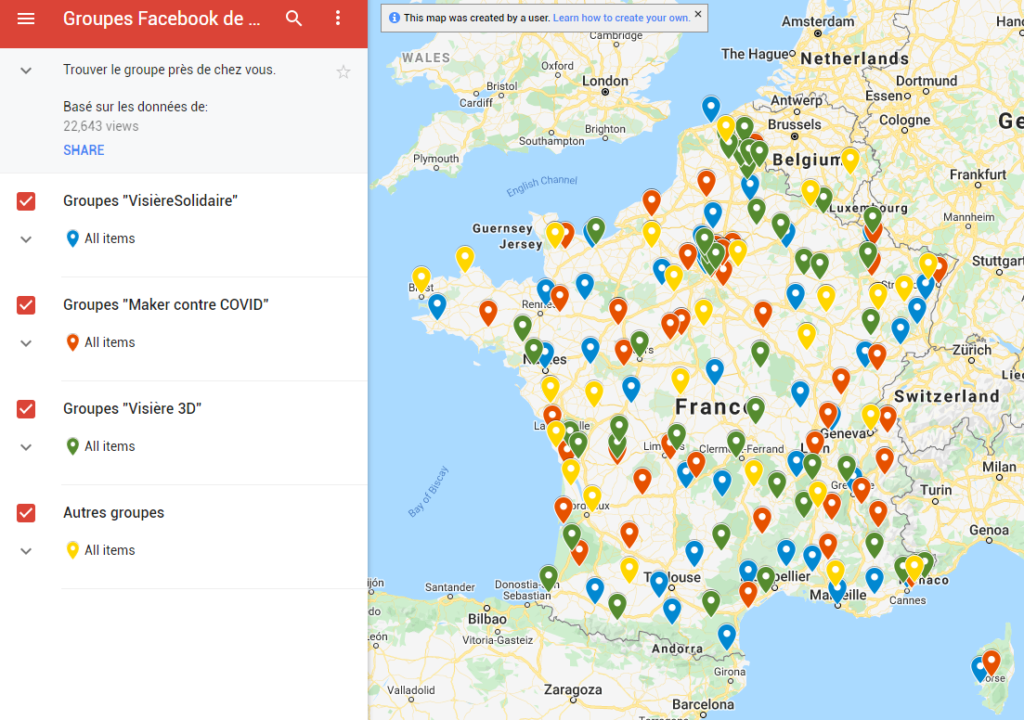

The general coagulation and collaboration between groups happened organically over time as the organizations began to recognize each other and share ideas and strategies. While there is no overarching organization or administration, the leaders of these organizations would frequently have video meetings to discuss shared plans. Facebook Groups popped up with 5000-7000 members each around France, and people banded together regionally in areas with around 60km in radius (see map of these regional groupings in “Data Management” below). Organizations like FabriCommuns, Fablabs, and Visere Solidaire were similar in that they helped organize the connection between healthcare workers and makerspaces and aided in facilitated supply routes.

Makers used their connections to small companies; FabLabs used their connections to larger companies, and people organically banded together to get designs validated as quickly as possible by hospitals. The FabLabs and JOGL worked and organized together, and utilized international volunteers like HelpfulEngineering, and partnered with smaller initiatives like FabriCommuns.

Covid3d.org is a project stood up by Parisian hospitals, and was designed specifically to help facilitate the distribution of 3d printers to help create PPE and through private donations were able to secure 2,000,000 euros to put towards printers.

The similarly named Covid3D.fr project was born out of Heliox’ YouTube and Facebook communities, and one of the largest 3d printer farm efforts stood up in France and in Europe with nearly 10,000 participants and 200,000 face shields produced; due to changing French legislation and stricter quality control requirements, it had to be permanently shut down in June 2020.

In the case of French FabLabs, there was a history of doing international human-centric collaborative work – building prosthetic hands for amputees and other “Human Labs” and “e-NABLE” type projects for many years before COVID. When the virus broke out, they set up a team on March 16 to address the crisis and build life-saving devices. There were lots of individual makers outside of the FabLab network and they tried to join forces. At the height of the project, nearly 1,000 designers worked day and night to design masks, shields or anything that could help (including ventilators).

On a regional scale, certification was possible quite quickly, and attempts were made to organize a “Shared factory” where 3D printers, fablab tools, but also companies resources would be used in a virtual factory network. The challenges were that some designs were validated only regionally through hospitals, and couldn’t be replicated nationally for legal approval reasons.

Leaders of that loose national coalition:

- Alexandre Rousselet – coordinator of regional fablabs across france.

- Anthony Seddiki – Co-Founder of Visiere Solidaire

- Bertrand Baudry – Curator for Maker Faire France

- Catherine Villeret – fabriCommuns Collective/Platform co-founder

- Constance Garnier – Covid Initiative Co-Founder – PhD student at Telecom Paris

- Matei Gheorghiu – French Fablab Network’s Scientific Council coordinator

- Matthieu Dupont de Dinechin – French Fablab Network Board Member

- Medard Agbayazon – Francophone Network of West African Fablabs (Co-Founder of MakersNordSud)

- Roman Khonsari – Paris Hospitals – Covid3d project – Surgeon

- Simon Laurent and Hugues Aubin – President and VP of French FabLab Network

- Sonia Scolan – Brittany Solidarity Network (Co-Founder of MakersNordSud)

- Thomas Landrain – Co-founder and CEO of JOGL (Just One Giant Lab)

- Yann Marchal – Founder of Makers Contre Le Covid

- Yann Vodable – Co-Founder of Visiere Solidaire

Management /Reporting Structure

Image: OSMS

National level organizations like Visere Solidaire and Fablabs help bridge the demand of healthcare workers and makers. They help facilitate volunteer supply lines to transport PPE to where it needs to go. On a smaller basis, they have also collaborated with the Military to deliver supplies.

Most all of the organizations are on a volunteer basis with people producing as they can and the larger organization trying to facilitate the best use and transportation of those supplies. Organizations like Fablabs that have more of a concrete network are more organized in terms of communicating and standardizing across makerspaces.

Networks like Fablabs and Visiere Solidaire have mostly worked locally to find the best local solutions for distribution and finding out the exact demand. They then worked together to create and establish the best possible supply routes and organization of makerspaces. On the large national scale, the various organizations keep a loose structure with various meetings between the leaders of the organizations to discuss the state of the movement and share ideas as to how to optimize production.

Within the organizations themselves, most organize through the individual regions in France; Fablabs for example has 234 members organized between 4 boards; from there, they have 15 separate sub-organizations throughout France that better react to the local conditions in those areas. Other places like Visiere Solidaire partner with local organizations that have formed in regions and will divert requests and demands to those structures in order to better facilitate communication and organization. Networks like Fablabs have a wide national scope since they had a pre-existing network and hierarchy which they utilized to convert FabLabs throughout France into mini-factories for PPE.

Places like Visiere Solidaire have very loose structures more or less serving as a central point of communication between existing smaller networks of makerspace communities. They do have a reporting structure though, as well as a way to manage some efforts, i.e. making face shields in a targeted fashion specifically for countries in South America in the case of Visiere Solidaire. Most outreach communication happened through Facebook Groups and Twitter. The internal organizing communication work was done on Mattermost, WhatsApp, Facebook Groups and Discord.

Data Management

Image: COVID Initiative

Image: COVID Initiative

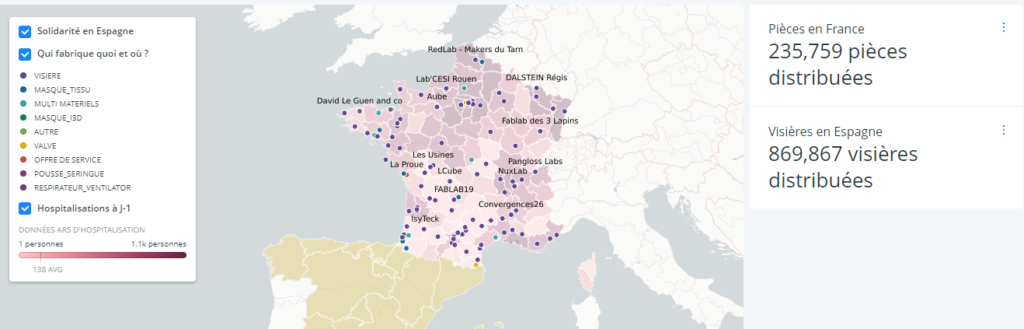

Networks keep track of national PPE production data within their own networks. Visiere Solidaire has tracked 900,000 maker-made Face Shield in its organization alone. They tracked their numbers through a large spreadsheet that Anthony Seddiki (the founder) managed and sub-groups across France reported to.

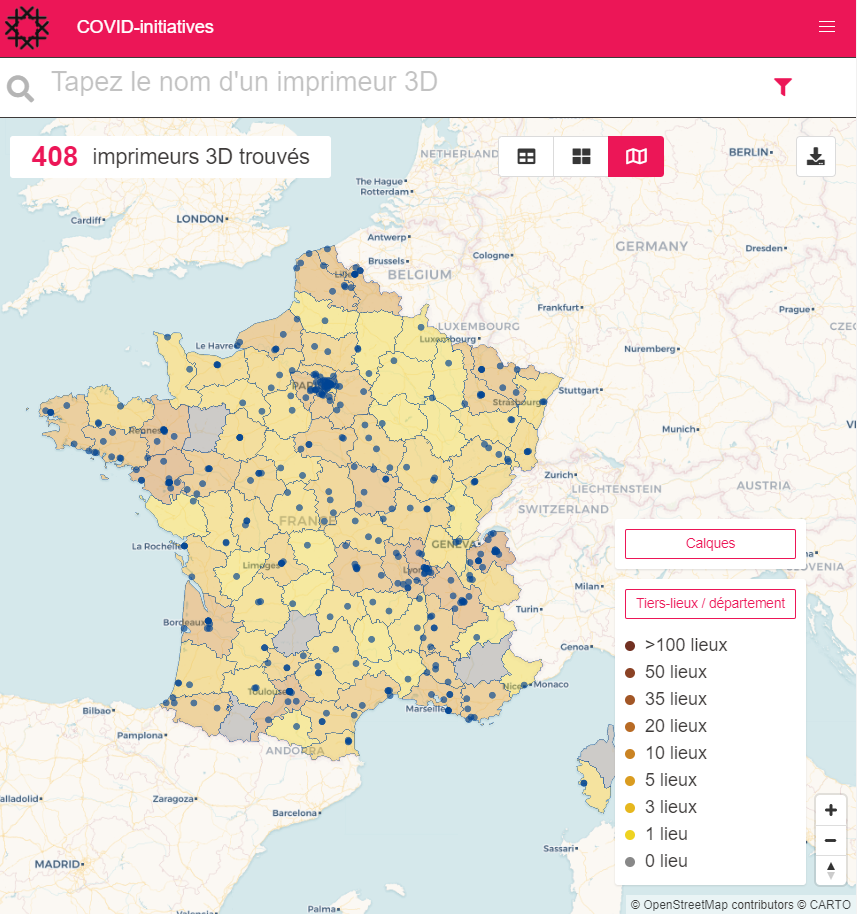

COVID Initiative is primarily a data-tracking project between organizations and even across country borders, powered by a team of 12 people that organize data. They for example created a capability map of most 3D printers in France, or a full map of labs in France together with solidarity projects in Spain. It also mapped the various regional affiliates of the 3 large Facebook Groups: Visiere Solidaire, Makers Contre COVID and Visiere 3D.

Makery wrote stories about a number of initiatives to spread awareness.

MakersNordSud mapped the FabLabs and hospitals in 6 African countries to aid the labs in distributing PPE once they had the capacity to. Data Visualization was done on a variety of platforms, but primarily custom GoogleMaps lists and Carto.

Image: COVID Initiative

Politics & Enablers

Towards the beginning of the crisis, the general group of organizations reached out to the national government for guidance regarding regulating and testing masks, but the government didn’t respond for a month and was entirely unhelpful.

From then on, they have had little interaction with the national government and have received some aid from the military to help facilitate transportation and supply lines. This was achieved in a particular region in France where the military could use their vehicles and circumvent the lockdown transport restrictions (the rule was you could not go further than 1km from your house without special authorization). More effectively, the organizations have collaborated with local governments and health services to coordinate creation and distribution. Some city governments provided funding for individuals to create “Solidarity Factories” by paying local sewists to make cloth masks.

The French government provided $4Bn at the beginning of the crisis to large industrials to build masks and respirators. Said industrial players could not ramp up any production in the first 30 days of the lockdown; not only was it difficult for their usual workflow, but little information was available about emergency clearance for PPE products in large scale production. The sourcing of research and development for devices is likely linked somewhere with tested and validated Open Source designs from around the globe, but early in the pandemic, few looked closer at the results of the state grant nor at the licences of the medical devices that should have been designed and built.

When the French government discontinued the state of emergency, they put severe limitations on maker-made PPE. By that point, large plastics manufacturers had been able to get market authorization for face shields and other PPE (usually it would have taken 6 months; due to the emergency, approvals took 2 months on average for commercial manufacturers). These large manufacturers have now largely fulfilled demand.

French fablabs and makers group have been associated by the Ministry of Economics to set up a guidelines for Anti-Projection Equipment (in French ”EAP”) and to have the right to make and build these objects during the time of sanitary state of emergency. While there has been local validation of medical devices in hospitals, no official program has been developed by authorities at the national scale.

The ecosystem of R&D, emergency fabrication processes and logistcs born during the crisis with multimodal fabrication channels (makers, fablabs, companies, industrials) are referred to as “Open Health” by the French FabLab leadership. They are pursuing further development of this concept – locally, nationally,and at the international level.

Funding

Only a couple organizations have built funding structures; most of the organizations that raised and needed money were those engaging in R&D.

The Covid3d project of Paris hospitals was able to raise over 2 million euros from private donations that went towards buying 3d printers to be used to create PPE, medical devices, and other devices deemed useful. MakersNordSud.org aims to reach a $175,000 budget for the equipment transfer to local FabLabs in Africa. Other organizations like JOGL utilized a system of grants and partnerships that would allow individual organizations to get access to funds to create and test various designs for open source masks and ventilators.

Links / Press

Read Further Case Studies

Brazil

Despite enormous infrastructure challenges, Brazilian makers have stood up a decentralized national response resulting in 1 Million + pieces of PPE made across hundreds of maker groups, with a growing nation-wide coalition.